Technical Library

RESOURCES V: Harpsichord editions

Entire Contents Copyright © 2007 CBHTechnical LibraryRESOURCES V: Harpsichord editions Entire Contents Copyright © 2007 CBH |

Harpsichord editions…

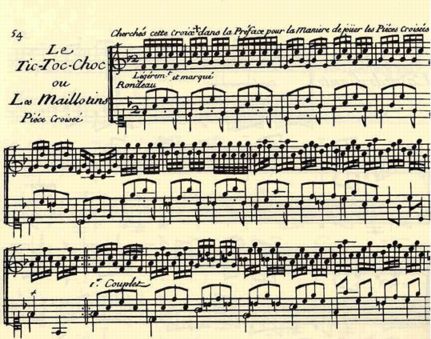

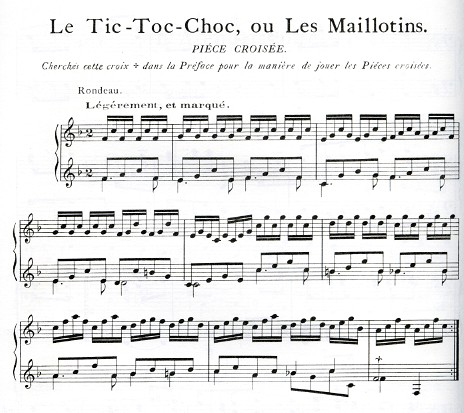

Of all the harpsichord repertoire, the works penned by the French Baroque composers were intrinsically wedded to the instrument. One of the most remarkable pieces in the entire harpsichord repertoire is François Couperin’s Le Tic-Toc-Choc ou Les Maillotins, a pièce croisée from his Dixhuitiéme Ordre published in his Troisième Livre of 1722.

The piece is discussed in Jane Clark and Derek Connon’s 2002 book, ‘The mirror of human life’: Reflections on François Couperin’s Pièces de Clavecin, where it is revealed that the Maillot were a famous family of rope-dancers. The authors quote Furetière’s Dictionaire universel:

| Tic toc; an indeclinable and artificial term, which expresses a beating, a reiterated movement, a pulse that beats, a horse that walks, the pendulum of a clock, a hammer that knocks. |

Reproduced here is just the refrain of the rondeau, which we’ll concentrate on: This scan was made from the facsimile edition published by Anne Fuzeau Productions, and as it is a direct photographic rendition, it obviously reproduces the elegant engraving of the original edition which was supervized by Couperin himself. It’s as close as we are going to get, unless we are fortunate enough to examine the original (or microfilm) ourselves from the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris—there’s no surviving manuscript.

The facsimile is just that, so it obviously preserves the original clefs—the familiar treble for the upper stave (right hand), and perhaps the not-so-familiar soprano for the lower, where the bottom line is middle c'.

It’s interesting to look at what various editors have done since with

this wonderful piece of music, some making it almost unrecognizable! The experience

should enable us to be wary of whatever we read on the page…

The composer kindly refers us to the preface of his third volume of harpsichord

pieces for instructions on how to play the piece. He writes:

The composer kindly refers us to the preface of his third volume of harpsichord

pieces for instructions on how to play the piece. He writes:

| In this 3rd book are to be found pieces which I call Pièce-croisées…those that are so designated should be played on two Manuals, one of which should be pulled out or withdrawn [ie uncoupled]. Those who have a Harpsichord with only one Manual, or a spinet, will play the upper part as written, and the Bass an octave lower; when the Bass cannot be taken an octave lower, then the upper part will have to be moved up an octave. Pieces of this kind, moreover, are suitable for two flutes or oboes, as well as for two Violins, two Viols and other instruments of equal pitch, it being understood that those who play them will adapt them to their own range. |

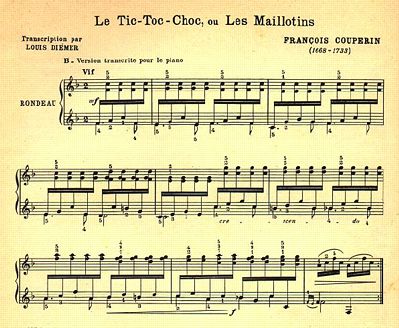

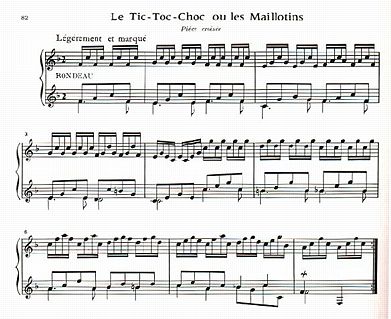

I’d like to think we could rely on the French, but here we have a French version from the series Les Clavecinistes Français, published by Édition Classique A Durand & Fils.

It’s nice that at least the man responsible for the edition, famous French musicologist Louis Diémer, is credited. Indeed, it is also acknowledged that is a “transcription for piano”. At least that’s honest!

Thanks, but no thanks: Mr Diémer has felt obliged to render the right hand “tic-toc-tic-toc” of the original into an offbeat block fifth, probably in an effort to keep the piece in the mid-keyboard area of the original, although he’s forgotten it’s impossible to hold the first left hand f' if we are going to chop away repeatedly with the right. Fingerings are kindly provided in the usual manner as though we are not capable or intelligent enough practices to decide our own, and there is the usual expressive goop that pianists seem to have trouble living without.

Sadly, we are so dumb that we couldn’t even recognize Couperin’s mordent sign, so the simple ornament must be written in full for us. Aghast! It’s also before, rather than on the beat as we would expect to hear today.

Many musicians, though, would be grateful to have familiar clefs for both

hands. (One possible version that I haven’t shown here, would be a performer-friendly

facsimile, where clefs have been modernized, and the original lower staff moved

up a line, preserving the appearance of the original.)

Instead, we must cross the Channel.

Instead, we must cross the Channel.

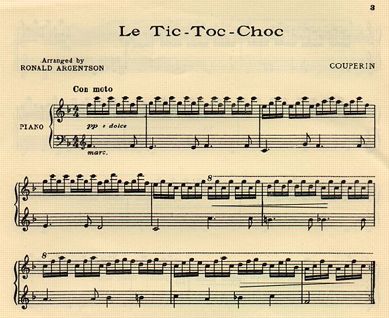

Here we have a 1933 arrangement by Ronald Argentson published by Leonard, Gould & Bolttler in London. It is #33 from The portrait gallery series.

While it is unashamedly pianistic, here is a version by a man that has obviously looked at something close to the original source, and preserved as much of the architecture of the music as he could. The right hand is unadulterated, but merely stuck up the octave as Couperin suggested for those who didn’t have a double-manual instrument. Very “authentic”!

However, the left hand texture is thinned somewhat.

It’s also interesting that he has decided the piece should begin very

softly and sweetly, rather than the previous hammered mf.

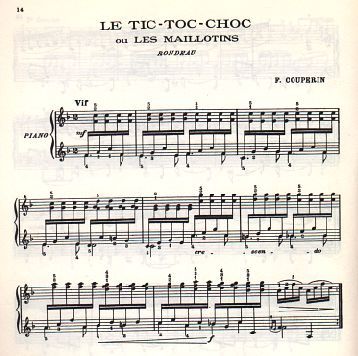

My next example was copyrighted in 1968, and is from Kalmus study score #888, French Composers for the Clavichord. That’s a misnomer that should

make you immediately suspicious—I’m not aware of many French composers

for the clavichord at all! The clavichord was not terribly popular in France.

My next example was copyrighted in 1968, and is from Kalmus study score #888, French Composers for the Clavichord. That’s a misnomer that should

make you immediately suspicious—I’m not aware of many French composers

for the clavichord at all! The clavichord was not terribly popular in France.

You can see this is an exact copy of the Diémer arrangement,

although it lacks any acknowledgement.

So what score can you reliably play from?

So what score can you reliably play from?

One of the best may well be one of the first: Edited by Brahms and Chrysander, this scan was made from the Augener edition, first published about 1888, and frequently reprinted.

The music is crisp and clear, almost sparse in appearance on the page without the expressive goop and fingerings of the other versions. (Of course, I couldn’t say this for some of the slower pieces which have Couperin’s ornaments on the ornaments…) The old soprano clef has been turned into something more familiar for the left hand.

These reasonably priced volumes of Couperin can often be found secondhand.

Maurice

Cauchie prepared an edition for Éditions de L’Oiseau Lyre from Monaco,

which was revized with reference to the original sources by Thurston Dart in

1968.

Maurice

Cauchie prepared an edition for Éditions de L’Oiseau Lyre from Monaco,

which was revized with reference to the original sources by Thurston Dart in

1968.

The clean appearance of the music is remarkably similar to the Augener.

For

many modern musicians, we can safely return to the French, and use the Heugel Le Pupitre series, the four Couperin volumes edited in the early 1970s

by Kenneth Gilbert.

For

many modern musicians, we can safely return to the French, and use the Heugel Le Pupitre series, the four Couperin volumes edited in the early 1970s

by Kenneth Gilbert.

This score shares the neat appearance of the antique Augener edition, but has the advantage of later scholarship and greater accuracy.

In the editor’s preface, mention is made of the special punches “cast in an attempt to reproduce as closely as possible the supremely elegant ornament signs of the original edition.”

We used to make the various harpsichord volumes of this Le

Pupitre series available. Ther was a wide variety of composers represented,

and my only wish was that the volumes were better bound. They are frequently

found on the shelves of musicians, despite their expense, and until a few years

ago when playing from facsimile became vogue, this quite fine edition was the

only way many composers were available.

| Carey Beebe performing an excerpt from François Couperin’s Le Tic-Toc-Choc ou Les Maillotins |

| Technical Library overview | |

| Harpsichords Australia Home Page |